兩篇關於這本怪書的文章,寫得不錯:

An Essay on Metamagical Themas

by Douglas Hofstadter

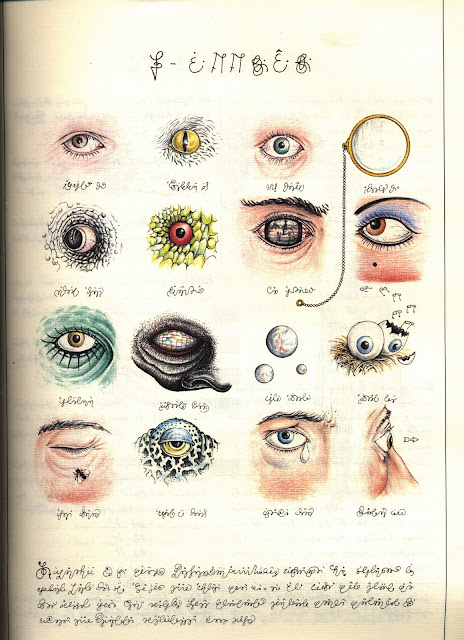

Codex Seraphinianus is ... a highly idiosyncratic magnum opus by an Italian architect indulging his sense of fancy to the hilt. it consists of two volumes in a completely invented language (including the numbering system, which is itself rather esoteric), penned entirely by the author, accompanied by thousands of beautifully drawn color pictures of the most fantastic scenes, machines, beasts, feasts, and so on. It purports to be a vast encyclopedia of a hypothetical land somewhat like the earth, with many creatures resembling people to various degrees, but many creatures of unheard-of bizarreness promenading throughout the countryside. Serafini has sections on physics, chemistry, mineralogy (including many drawings of elaborate gems), geography, botany, zoology, sociology, linguistics, technology, architecture, sports (of all sorts), clothing, and so on. The pictures have their own internal logic, but to our eyes they are filled with utter non sequiturs.

A typical example depicts an automobile chassis covered with some huge piece of what appears to be melting gum in the shape of a small mountain range. All over the gum are small insects, and the wheels of the "car'' appear to have melted as well. The explanation is all there for anyone to read, if only they can decipher Serafinian. Unfortunately, no one knows that language. Fortunately, on another page there is one picture of a scholar standing by what is apparently a Rosetta Stone. Unfortunately, the only language on it, besides Serafinian itself, is an unknown kind of hieroglyphics. Thus the stone is of no help unless you already know Serafinian. Oh well... Many of the pictures are grotesque and disturbing, but others are extremely beautiful and visionary. The inventiveness that it took to come up with all these conceptions of a hypothetical land is staggering.

Some people with whom I have shared this book find it frightening or disturbing in some way. It seems to them to glorify entropy, chaos, and incomprehensibility. There is very little to fasten onto; everything shifts, shimmers, slips. Yet the book has a kind of unearthly beauty and logic to it, qualities pleasing to a different class of people: people who are more at ease with free-wheeling fantasy and, in some sense, craziness. I see some parallels between musical composition and this kind of invention. Both are abstract, both create a mood, both rely largely on style to convey content.

An Essay on the Codex Seraphinianus

In the beginning there was language. In the universe that Luigi Serafini describes, I believe the written word came first: that flowing script penned with such precision, which we come so close to understanding but which nevertheless eludes our grasp.

The anguish triggered by this Other Universe derives less from its unfamiliarity than from its unnerving resemblance to our own world. So too with the writing, which is believable enough to belong to some alien but not unfeasible linguistic zone. On reflection, one realizes that the peculiarity of Serafini's language is not just in its alphabet, but in its syntax as well. The universe evoked by this language, as illustrated in the encyclopedia's plates, almost always contains things that we recognize; it's their relation to one another, the bizarre juxtaposition of these things, which strike us as strange. (I say "almost always'' because there are also unrecognizable forms which serve a very important function, as I'll try to explain later on). The crucial point is this: if Serafini's language has the power to bring life to this world whose syntax is so alien to us, then beneath the mystery of its indecipherable surface it must contain an even deeper mystery that concerns the internal logic of language and thought.

In this fantasy world images assume many layers of meaning and the confusion of the visual components creates monsters: Serafini's universe is teratological. But even teratology has its own logic, the thread of which seems to surface and disappear like the meanings of these words so diligently written with the tip of my pen.

Like Ovid of the "Metamorphosis,'' Serafini believes in the continuity and permeability of all areas of existence. The anatomical and mechanical exchange morphologies: instead of hands, a human arm will end in a hammer or a pair of pincers; legs are supported by wheels, not feet. The human and vegetal complete each other. Take the plate on the cultivation of the human body. We see trees growing from a head, grass sprouting from the palm of a hand, and carnations bursting from an ear. The vegetal world unites with everyday objects to produce plants with scissor leaves and matchstick fruit. The zoological joins with the mineral, and we have partially petrified dogs an horses. Fantasy and technology are united, as are primitive

and urban, written words and living organisms.

Just as certain animals assume the form of other species who share their habitat, so too human beings become contaminated by the objects around them. The passage from one form to another is graphically described in one of Serafini's most successful visual inventions: the

image of the mating couple whose bodies gradually merge and become transformed into a large reptile. My other favorite images are the chair-tree, the school of fish whose partially surfaced forms look like giant movie-star eyes on the water, and all the figures that contain a rainbow theme.

There are three images at the heart of Serafini's visionary ecstasy: the skeleton, the egg, and the rainbow. The skeleton is the only core of reality that remains in this world of interchangeable forms. We see skeletons waiting to be clothed in flesh; when the process is complete, they gaze in bewilderment at their filled-out bodies. Another plate conjures up a city of skeletons, with television antennas made of bones and a skeleton waiter serving a plate of bone soup.

The egg is the original element, and it appears with and without its shell. Raw eggs drop from a tube and become autonomous moving objects that creep along the ground, climb a tree, and then fall down again, assuming the appearance of fried eggs.

The rainbow has a central place in Serafini's cosmology. As a solid bridge, it can support an entire city; but it's a city that changes color and substance with the rainbow itself. From the rainbow come tiny, multi-colored creatures of strange shapes, which might very well be the vital force of this universe, the generative corpuscles in the unrelenting process of metamorphosis.

Other plates depict a helicopter-like object which is used to draw rainbows in the sky---not only in the classic semicircle shape but also in the form of a knot, a spiral, a zigzag, a curlicue. Those same multi-colored corpuscles hang on thin threads from the fuselage of this apparatus. Are they mechanical specks or iridescent dust suspended in air? Or are they a kind of bait used to catch colors? These are the only indefinable forms we come across in Serafini's cosmography.

Similar forms of luminous bodies (photons?) swarm from lights or appear as micro-organisms carefully catalogued in the beginning of the sections on botany and zoology. Perhaps they are graphic symbols and in fact constitute yet another alphabet, even more archaic and mysterious. Perhaps everything that Serafini shows us is a form of writing, and only the code varies. In this writing-universe, roots that seem almost identical are given different names, because each one is a separate sign. Plants twist their stems like lines penned on a piece of paper. They dive back into the earth only to sprout out again or to blossom underground.

Serafini's fantastic plant life is an extension of the imaginary botanical world of Edward Lear's "Nonsense Botany'' and Leo Lionni's "Botanica Parallela.'' In his greenhouse we discover the cloud plant that waters its own flower, and the spider web flower that catches insects. Trees uproot themselves and jump in the sea, using their roots like a boat's propeller.

Serafini's animal life is always nightmarish. Its evolution is ruled by metaphors (the sausage-like snake, the viper-shoelace tied on a sneaker), metonymy (the bird that is actually a pen with a bird's head), and the condensation of images (the pigeon in the form of an egg). After the zoological monsters we come to the anthropomorphic ones, perhaps some failed experiment along the path to humanization. The great anthropologist Leroi-Gourhan explained that the process of humanization began in the feet. Serafini's illustrations depict perfectly-evolved feet and legs, but instead of leading to a torso they finish in the form of an umbrella, a ball of yarn, or a bright star. In one of the book's most mysterious images, these star-creatures are shown standing alone in boats that drift down a river, passing beneath the huge arch of a bridge.

The sections on physics, chemistry, and mineralogy are the most relaxing, because their images are more abstract. But the nightmare returns in the engineering and technology pages. Monstrous aberrations are no less disturbing in machines than in man. When we come to the social sciences (which include ethnography, history, sports, linguistics, gastronomy, and urban studies), we must bear in mind that by now men and objects are inextricably linked in an anatomical continuity. There's even the perfect machine that satisfies all of man's needs, and which turns itself into a coffin at the time of death.

Ethnography is no less horrifying than the other fields. Among the various types of primitive species catalogued here we find the garbage=dwellers, the rodent-skin wearers, and, most dramatic of all, the man-road, dressed in asphalt with a white line down the middle.

The anguish at the core of Serafini's imagination probably reaches its peak in the study of gastronomy. Yet, even here we detect his special brand of humor, especially with such inventions as the toothed plate that pre-chews food so it can be sipped through a straw, and the kitchen faucet that delivers an endless supply of fresh fish.

It seems to me that for Serafini linguistics is the most poetic of fields, the true "gaia scienza'' (especially the written word; the spoken word remains a source of anxiety, and we see it as black mush oozing from lips, or as dark squiggles being fished from a gaping mouth). The written word is a living thing (blood spurts when you prick it with a pin), and it enjoys an autonomy that lets it fly off the paper on little balloons or parachutes. Some words have to be sewn down to make them stay. And when writing is examined under a microscope, the fine lines assume another meaning: one letter is a highway, another is a stream quivering with fish, and another is bursting with crowds of people.

In the end, as we see in the final image of the Codex, the destiny of every written work is to disintegrate into dust, while all that remains of the writing hand is its broken skeleton. Lines of words break off the page and crumble to the ground. But from the piles of dust tiny rainbow-colored forms emerge and begin to leap above the debris. The vital force of all the alphabets and metamorphoses resumes its life cycle.